- Index

- Autograph Type

- Binding

- Industry

- Signed

- Signed By

- Absalom Baird (4)

- Ambrose Burnside (9)

- Charles Devens (2)

- Doris Kearns Goodwin (2)

- Frederick Phisterer (3)

- General Fitzhugh Lee (2)

- Gordon Granger (2)

- Henry Mizner (3)

- Jack Davis (4)

- John A. Dix (5)

- John Geary (2)

- John Parke (2)

- Nathaniel Banks (2)

- Neal Dow (3)

- Nelson A. Miles (2)

- Oliver O Howard (2)

- Philip Sheridan (3)

- Robert Anderson (18)

- Sitter (17)

- Thomas Kane (2)

- ... (4164)

- Topic

1860's GENERAL ROBERT ANDERSON Civil War CDV PHOTO from Gen. Geo. Crosman Album

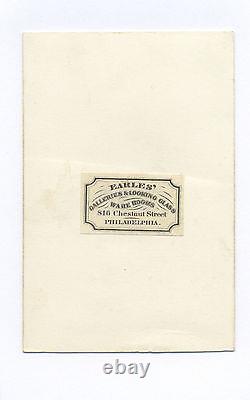

We are offering in this listing one original 1860's Civil War cdv sepia albumen photo of General Robert Anderson. The back has the photographer's marking Earles' Galleries & Looking Glass Ware Rooms 816 Chestnut Street Philadelphia.

Robert Anderson was born on 14 June 1805 & died on 26 October 1871. Anderson was an American military leader. He served as a Union Army officer in the American Civil War, known for his command of Fort Sumter at the start of the war. He is often referred to as Major Robert Anderson, referring to his rank at Fort Sumter.

In 1871 he died in France, at the age of 66. This cdv is one part of a 98 piece collection of cdv photos that was formed during the Civil War and slightly after by General George Hampden Crosman & his wife. The Crosman album contained a number of scarce & elusive cdvs of Union generals as well as a number of cdvs of Union generals with original autographs. This cdv measures 3 3/4 inches tall by 2 7/8 inches wide. The front bottom edge of the matt has, in period, penciled identification in an unknown hand.

There is some minor wear at the top edge of the matt. There are two faint bend lines on the background of the photo which show up much more in our scan than they show up in the actual photo. They are much more subtle on the actual photo & they do not break the surface at any point.

There is a tiny bit of, in period, trim to the bottom border of the matt performed to expedite album insertion. Our inventory number of this item is #5844. Is an estimate and the actual cost may differ. International Buyers - Please Note.General Robert Anderson When South Carolina seceded In December 1860, Major Anderson, a pro-slavery, former slave-owner from Kentucky, remained loyal to the Union. He was the commanding officer of United States Army forces in Charleston, South Carolina - the last remaining important Union post in the Deep South. Acting without orders, he moved his small garrison from Fort Moultrie, which was indefensible, to the more modern, more defensible, Fort Sumter in the middle of Charleston Harbor. South Carolina leaders cried betrayal, while the North celebrated with enormous excitement at this show of defiance against secessionism. In February 1861 the Confederate States of America was formed and took charge.

Jefferson Davis, the Confederate President, ordered the fort be captured. The artillery attack was commanded by Brig. Beauregard, who had been Anderson's student at West Point. The attack began April 12, 1861, and continued until Anderson, badly outnumbered and outgunned, surrendered the fort on April 14. The battle began the American Civil War.

No one was killed in the battle on either side, but one Union soldier was killed and one mortally wounded during a 100-gun salute. The modern meaning of the American flag, according to Adam Goodheart (2011), was forged in December 1860, when Anderson, acting without orders, moved the American garrison from Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter, in Charleston Harbor, in defiance of the overwhelming power of the new Confederate States of America.

Goodheart argues this was the opening move of the Civil War, and the flag was used throughout the North to symbolize American nationalism and rejection of secessionism. But in the weeks after Major Anderson's surprising stand, it became something different. Suddenly the Stars and Stripes flew -- as it does today, and especially as it did after the September 11 attacks -- from houses, from storefronts, from churches; above the village greens and college quads. For the first time American flags were mass-produced rather than individually stitched and even so, manufacturers could not keep up with demand. As the long winter of 1861 turned into spring, that old flag meant something new. The abstraction of the Union clause was transfigured into a physical thing: strips of cloth that millions of people would fight for, and many thousands die for. Anderson's actions in defense of American nationalism made him an immediate national hero. He was promoted to brigadier general, effective May 15. Anderson took the fort's 33-star flag with him to New York City, where he participated in a Union Square patriotic rally that was the largest public gathering in North America up to that time. Anderson then went on a highly-successful recruiting tour of the North. His next assignment placed him in another sensitive political position, commander of the Department of Kentucky (subsequently renamed the Department of the Cumberland), in a border state that had officially declared neutrality between the warring parties. He served in that position from May 28, 1861. Historians commonly attribute failing health as the reason for his relinquishment of command to Brig. Sherman, on October 7, 1861. But a letter from Joshua Fry Speed, Lincoln's close friend in Louisville, Kentucky, suggests Lincoln's preference for Anderson's removal.Speed met with Anderson and found him reluctant to implement Lincoln's wishes to distribute rifles to Unionists in Kentucky. Anderson, Speed wrote to Lincoln on October 8, seemed grieved that [he] had to surrender his command. [but] agreed that it was necessary and gracefully yielded.

General Anderson's last assignment of his military career was as commanding officer of Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island, in August 1863. By coincidence, Fort Adams had been General Beauregard's first assignment after his graduation from West Point. Anderson officially retired from the Army on October 27 1863, and saw no further active service.